New research undertaken for this week’s National Summit on Women’s Safety finds violence and unwanted sexual activity are far more common among young women experiencing financial hardship than women who are not.

It comes as the federal government has denied Australians locked down and living only on benefits such as JobSeeker the sort of extra support it offered last year, when it effectively doubled JobSeeker during the early months of the pandemic.

Our findings of a higher risk of violence for women living in financial hardship is a real concern, especially when coupled with 2020 research from the Australian Institute of Criminology.

That research found that of the Australian women who reported physical or sexual violence from a partner during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, 65% experienced an increase in the severity or frequency of violence, or experienced it for the first time.

Abuse twice to three times as likely

Our research, using data from women aged 21-28 collected for the 2017 Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, found 14.4% had experienced some form of abuse at the hands of a current or former partner in the previous 12 months.

The definition of abuse includes physical, emotional and sexual abuse, coercive control, harassment and stalking.

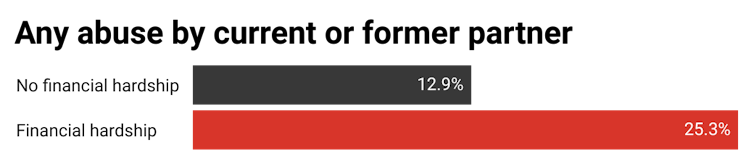

Among young women not reporting financial hardship, the rate was 12.9%. Among young women in financial hardship, it was 25.3%.

We characterised women as experiencing financial hardship if they reported they had been “very” or “extremely” stressed about money in the past 12 months and also said it was “difficult all the time” or “impossible” to manage on their income.

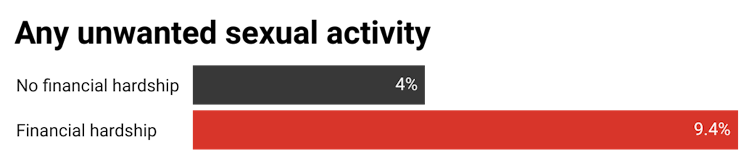

Overall, 4.6% of young women said they had been the victim of unwanted sexual activity in the previous 12 months.

Among young women not reporting financial hardship, the rate was 4%. Among young women in financial hardship, it was 9.4%.

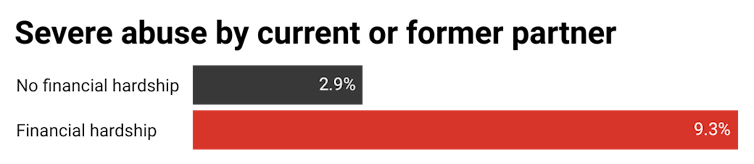

Overall, 3.7% had experienced at least one form of severe abuse at the hands of a current or former partner in the previous 12 months.

The definition includes being threatened or assaulted with a gun, knife or other weapon, being locked in a room, and being choked.

Among young women not reporting financial hardship, the rate was 2.9%. Among young women in financial hardship, it was 9.3%.

Abuse also leads to financial hardship.

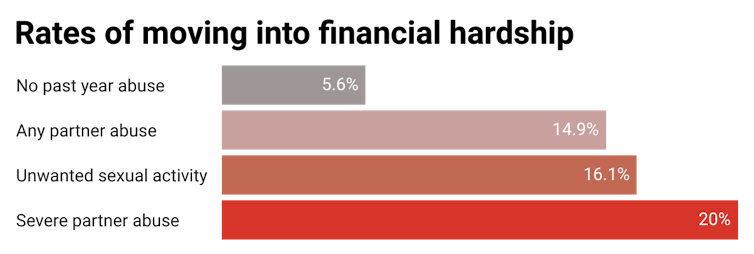

To examine this we compared rates of abuse among young women who had been free of hardship the year before.

Among young Australian women aged 21-28 who were not experiencing financial hardship in 2016, the risk of moving into financial hardship in 2017 was 5.6% for women who had experienced no abuse in the past year.

Among women who had experienced unwanted sexual activity, the rate was three times as big — 16.1%, compared to 5.6%.

Among women who had experienced severe partner abuse, the rate was almost four times as big — 20%, compared to 5.6%.

The research builds a strong case for governments to continue to invest in programs including helplines and counselling to address violence against women, a case made stronger by COVID-19.

COVID has created new opportunities for agencies to move quickly with innovative, fast-moving partnerships, such as those seen between police and health departments.

But to enact real change, it will be necessary to look beyond dealing with perpetrators and supporting victims.

The causes of partner violence against women include broader power imbalances, among them the idea of “women’s work”, uneven family responsibilities, paying women differently, and ignoring unpaid care work.

In Australia, institutionalised gender divisions of labour in the home and at work entrench disadvantage. World Economic Forum data shows Australia’s overall score on gender disadvantage going backwards.

This article appeared originally on The Conversation. You can read it here.