- Built Environment

- Employment

- Health

- Policy

- Journal Article

Regional Coronavirus Hotspots During the COVID-19 Outbreak in the Netherlands

Published: 2021

In the 1990s, central Dandenong in Melbourne’s southeast was in decline. But, over the past decade and a half, this trend has been halted and in some areas reversed. Our research has identified key elements in this revitalisation, including strong roles for both public sector and non-government participants.

Importantly, the approach has delivered new opportunities for the culturally diverse local community.

At the time these efforts began, a shrinking manufacturing sector and poor urban planning decisions had drained vitality from the centre. New shopping malls and suburban estates enticed people to live and shop elsewhere. Public spaces were dilapidated. Many retail buildings were vacant.

Unsurprisingly, local population levels were stagnating. Affordable rents and a community with strong networks of support attracted some new residents, most from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. However, once settled, many people faced barriers to employment, training and adequate public facilities.

The Victorian government and the City of Greater Dandenong were keen to reverse these trends. They wanted to reinstate the neighbourhood as Melbourne’s second-most-important urban centre. The state government funded the Revitalising Central Dandenong project from 2006.

Since then, and particularly since 2011, the process has also been propelled by local government action and the coordinated efforts of local leaders. They represent business, education, faith communities and social services. These interlinked activities across sectors have arguably been effective in kick-starting the project.

However, some important shortcomings have limited the potential for revitalisation. In particular, the benefits have not reached all of the community.

For example, many female migrants have not had access to suitable employment opportunities. Services are lacking for some marginalised community members, including asylum seekers.

Other concerns include persistent barriers to retail activation (including rising rents and parking costs), emergent threats of gentrification and a lack of major private investment in residential and office development.

Our research briefing explains our findings in detail, including some of these problems.

A significant one-off Victorian government investment of A$290 million was the cornerstone of the project, and it has been carefully designed. Experienced professionals appointed to the government development agency, then known as VicUrban, crafted the program.

The early focus was on catalyst projects and the removal of roadblocks to the considered development to follow. These actions included:

Given the entrenched decline, revitalisation was unlikely to occur without significant public commitment.

Following the state government’s energetic program start, the local government has taken the reins since 2011. The council gave priority to revitalising works in the centre (see the table of major project spending below) and to covering gaps in the original strategy. This included a housing strategy in response to emerging gentrification.

Because macro-policy in urban planning often fluctuates, local communities cannot depend on secure, long-term funding for discretionary renewal projects. To achieve revitalisation through redistribution, local government leadership is vital for maintaining focus on one area over others.

Refined skills in urban planning strategy and financial management have also been indispensable to the project.

The public program was enhanced because community leaders already knew each other and were predisposed to work together. They ranged from education providers (such as Chisholm TAFE and Deakin University) and faith groups (such as Interfaith Network) to trade associations (such as South East Melbourne Manufacturers Alliance) and private sector groups (such as the Committee for Dandenong). These groups worked both together with and separately from the publicly funded program.

Active and organised local leaders provided vital input on strategy design, partnered or led delivery of specific initiatives and put their organisations to work on gaps in the program. They also powerfully advocated for governments to remain focused on revitalisation.

Overall, these strong local networks enabled smoother policy development and delivery. Having an organised and receptive community to engage with was important.

Our research underscores the value of acknowledging the effectiveness of existing local strategies and community capacities. It highlights the need to work collaboratively. This includes a focus on the “soft side” of practice – that is, building relationships.

Enhanced opportunities have been created for many culturally and linguistically diverse communities. How so?

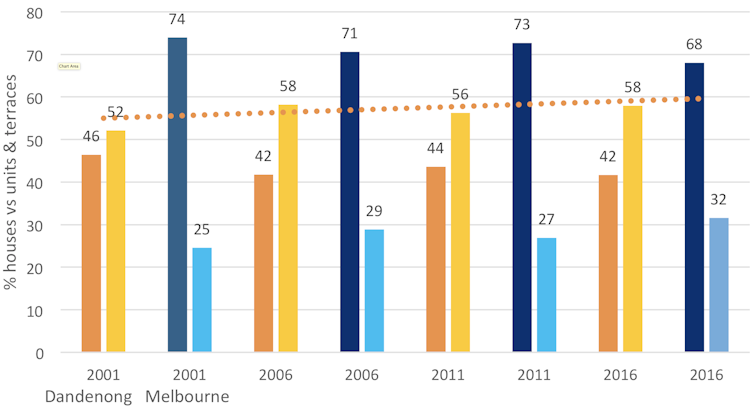

Diversity in housing types in Dandenong and Greater Melbourne

Our forthcoming analysis on Policy Forum further explains the ethic of cultural pluralism in policy and society.

Overall, urban centres cannot avoid fallout from broader economic restructuring, nor are they immune to poor strategic planning decisions or funding cuts that affect their prospects. Central Dandenong shows revitalisation can occur despite significant disadvantage. It has been achieved through a combination of public sector leadership and an interconnected and active local community.

This article appeared originally on The Conversation. You can find it, here.

This page was printed at 4:11 pm on Tuesday, 13 Jan 2026.

Please see https://lifecoursecentre.org.au/publications/comeback-city-lessons-from-revitalising-a-diverse-place-like-dandenong/ for the latest version.

© COPYRIGHT 2026. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.